Herds vs. the Efficient Market Hypothesis

One of my neighbors told me that she bought Tesla shares and Bitcoins at our building’s summer rooftop party a couple of years ago. The sole reason she bought the shares was because all of her friends had bought shares and she bought Bitcoins because Elon Mask recently tweeted that it was a buy. But the logic behind her reason was merely simple – things cannot go wrong if most of the people around us are doing it. Bitcoin? Elon Mask is so intelligent, so how could he be incorrect? Well, both Tesla stocks and Bitcoin turned out to be quite volatile for the next few years after she bought them. At another similar but less finance related event, I went shopping with a friend and he stated he was explicitly looking for a particular jacket solely because it was the trend in his office. Yes, peer pressure is real and to some extent, we all make some decisions driven by our peers instead of based on rationality. It reminds me of a well-known conformity experiment conducted by a psychologist, Solomon Asch, in the early 1950s.

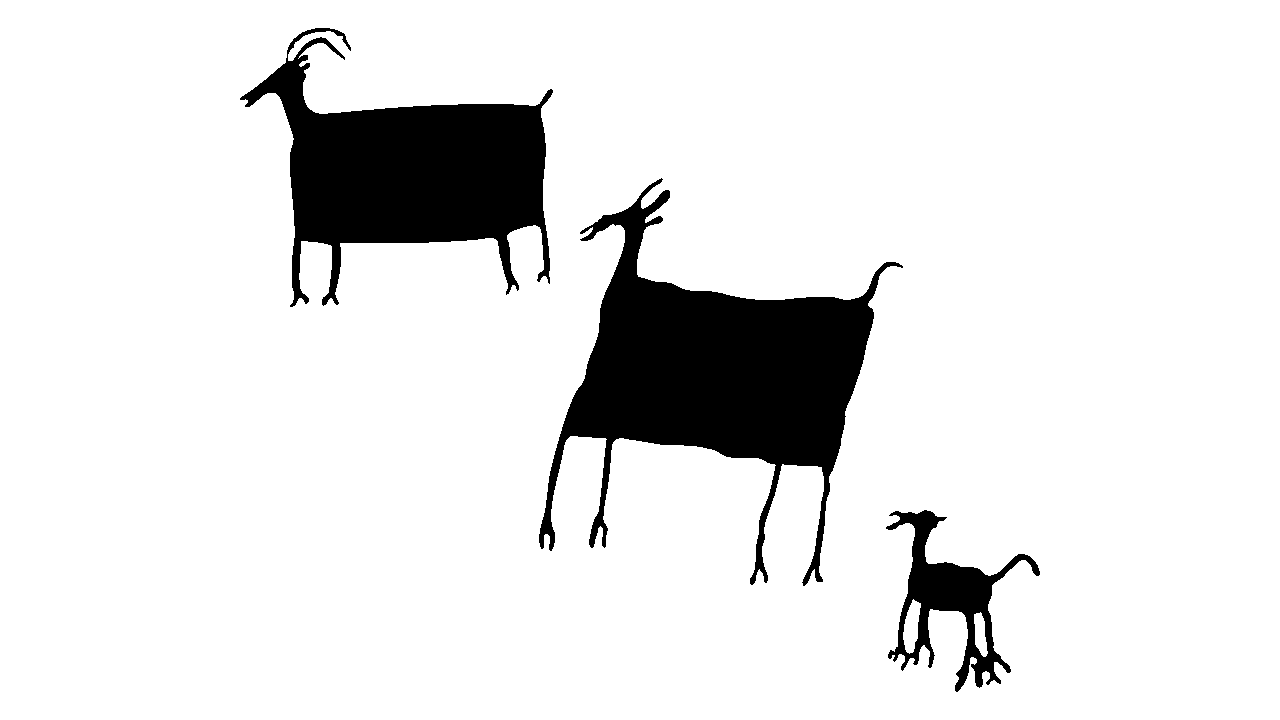

The experiment was an examination on herd behavior of humans. Asch invited the Swarthmore College students and divided them into groups of seven to nine participants in a classroom setting. Each group will see two cards: card A shows one straight line, and card B has three straight lines of different lengths where one line has the same length as the line in card A. The instructor would go around and ask the survey participants to identify the line of same length in card B. Although the answer should be clear right away, the majority of survey participants chose the most commonly picked lined by the group despite this line is clearly different in length.

Of course the experiment was not trying to demonstrate that humans are incapable of identifying linear lines of obvious differences in length. Instead, each of the survey group only had one real participant. The rest were all volunteers and were instructed to pick a wrong answer. As a result, 37% of real participants chose the answers that were picked by the majority of their groups rather than believing in their own judgement. The experiments were conducted multiple times across different locations and time periods with slightly different settings, and they all had similar findings. In 1953, NYU founds more than 20% of the participants gave the wrong answer just by an instructor telling them the “correct” answer even without blending them into groups with experiment volunteers. Regardless of the immediate clear identification, a reasonable proportion of the survey respondents incorrectly identified the difference merely because of the information they received from their surroundings.

The phenomenon of herd behavior violates Eugene Fama’s Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). With the infamous assumption that all investors are rational, EMH states that all stocks are fairly traded because prices reflect all available information and investors cannot outperform the markets. If the market is efficient and stocks are fairly priced, rational investors theoretically should buy the stocks that are underpriced and sell the ones that are overpriced. By doing so, it drives the market to an equilibrium and keeps it efficient. Unfortunately, this does not explain the two recent financial crisis.

One example comes to mind is the dot-com bubble. During the period of rising tech stock valuations, many investors foresaw that the stock market was in a speculative bubble. As opposed to efficient market view of finance where one should sell these overpriced stocks, many professional money managers had the mentality that excess returns could be easily generated if investor get out before the bubble burst (which could be true), they kept speculating on the tech stocks, followed by the noise trades, eventually led to the burst of the bubble.

The 2008 housing crisis was another violation of the EMH and it could be explained in the lens of herd behavior. Despite all signs of the housing bubble, home buyers kept taking subprime mortgages and bankers kept lending them, eventually creating a crisis that spilled over to the entire financial market. Could no one have predicted the catastrophic consequences of this speculation and exit the game before it burst? No problem, you exit, someone else would have quickly filled your place and taken your profit because the common sense was that everyone was doing it, if bad things happened to me, it would have happened to everyone. These examples discredit the EMH.

Asch concluded after his conformity experiment that “common sense, to be productive, requires that each individual contributes independently out of his [her] experience and insight”. In the perspective of the financial market, if the market was truly efficient, it demands all investors participate in the game independently rather than act as a herd.